Should We Prepare Future Physics Teachers to Advocate for Effective School Policies?

Kelli Warble, American Modeling Teachers Association and Arizona State University

Recently I have been struggling to answer the following question: Should physics teacher preparation programs educate future teachers about policy matters that are certain to affect their work as educators?

Ten years ago, when I was still in my high school classroom teaching mathematics and physics, I would not have considered policy advocacy to be part of my duties. But my experiences since becoming the Physics Teacher in Residence at Arizona State University (ASU) have made me realize that teachers negotiate policy issues more often than commonly recognized. And many of these issues have a significant impact upon students.

Does a district require all physics courses to have a common assessment? Is a school considering whether to transition to block scheduling? Does the state require a certain number of science courses be completed for graduation? Are science classrooms being remodeled, and if so, are effective classroom practices being considered in designing the new layout?

These are all policy considerations about which teachers are not commonly consulted. Yet decisions about these issues have a huge impact on an educator’s ability to foster valuable learning experiences for students.

In late 2016, I was a member of a task force convened by the American Association of Physics Teachers (AAPT) to articulate ways to leverage physics teachers as agents of change in education. As we worked to identify characteristics of teacher leaders, we found three arenas that were influenced by the leadership of exceptional educators (see Figure 1). The first two arenas were (to me) not surprising—instances of remarkable leadership in physics instruction and professional teacher associations. What I had not considered before was the potential for teacher leaders to affect policies at the local, state, and national levels.

Figure 1 Task force priorities build arenas of Teacher Leadership

Our task force subsequently collaborated on Aspiring to Lead: Engaging K-12 teachers as agents of national change in physics education,1 a report released by the AAPT in 2017. This report became an inspiration to me: I began a graduate program to pursue a Master’s in Science and Technology Policy at Arizona State University. My studies led me to an internship with AAPT where I was privileged to work with Rebecca Vieyra (then the AAPT K-12 Program Manager) as she successfully spearheaded a new policy fellowship for teachers.

The result was the first cohort of AAPT/AIP Master Teacher Policy Fellows selected in the spring of 2018.2 I was honored to assist with a 10-day policy workshop for these teacher fellows in Washington, DC in July 2018. My experiences with this initiative caused me to re-examine my views about teachers as policy advocates and the role of teacher preparation programs in this arena.

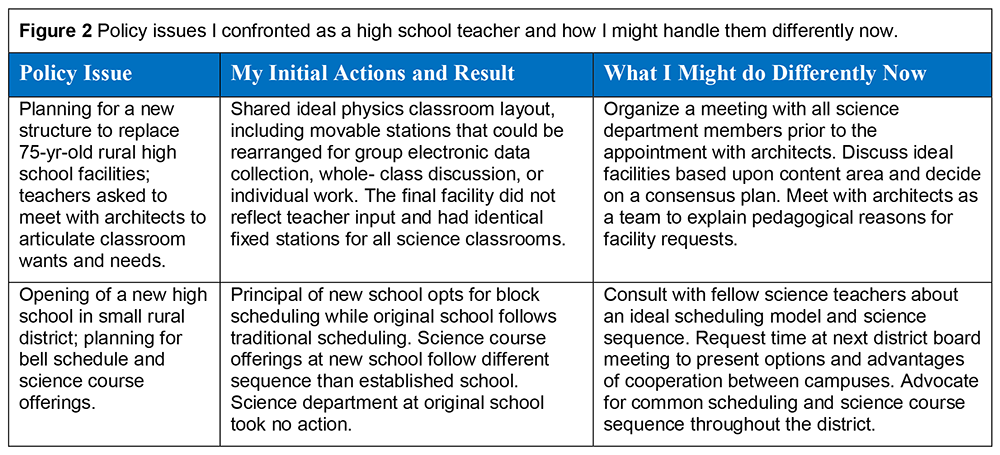

I now recognize that many of my most frustrating experiences as a high school teacher centered on policy decisions that I felt helpless to address (see Figure 2). Had I been trained to recognize the importance of policy decisions and to advocate more effectively, would there have been different outcomes? Would this preparation have benefitted my students?

Although I am a novice to policy leadership, I was able to “mentor” several Arizona teachers by encouraging them to apply for the AAPT/AIP Policy Fellowship, and these teachers were subsequently selected for the program.

This group of Arizona teachers is now advocating to “Save Arizona Physics” and may potentially influence not only students in their individual classrooms, but also students throughout our state. Their experiences and reflections demonstrate insights that I aspire to stimulate in the pre-service physics teachers in our teacher preparation program at ASU.

The potential benefits of preparing teachers to become savvy to policy issues might best be reflected by the experiences of policy fellow Amanda Whitehurst. Amanda taught elementary and middle school science for 14 years and is currently on a break from teaching to raise her children. She recently became the President of STEMteachersPHX, a local group focused on networking and professional development for STEM teachers.

Amanda: “[I] want to talk…about the paradigm shift that happened over the course of our 10 days in DC. The big takeaway is, as teachers, we already have the skills we need in order to effect change. We just need to make sure that we're networking, that we are very prepared and knowledgeable, and that we build a coalition of people who are all working towards the same goal. And in our state, that can seem like…an insurmountable task sometimes—but really, everybody wants to have good education…[but] they differ in how they want to accomplish that goal. We have to put a goal in front of them that everybody can agree on and find a path towards that goal.”

Amanda’s reflections spurred me to consider the benefits of including discussions of how policy decisions affect the physics classroom in our teacher preparation programs. Is it ethical to send teachers to the classroom without preparing them to advocate for policies that will ensure access to a high-quality physics education for all students? Is it appropriate for physics teachers to engage in policy debates?

In the final analysis, I worry that we, as a physics teaching community, must step up to advocate for effective policies for science education. Failure to do so risks continued implementation of policies which gradually degrade our ability to be effective educators.

Kelli Warble has taught high school and college physics and mathematics for 25 years in the Phoenix area. She became the full-time physics Teacher in Residence (TIR) at Arizona State University in 2012. She currently serves as the TIR at Arizona State while pursuing a Masters’ degree in Science and Technology Policy. She is President Elect of the American Modeling Teachers Association.

(Endnotes)

1. AAPT/AIP Master Teacher Policy Fellows. (2018, April). Retrieved December 1, 2018, from https://www.aapt.org/K12/Aspiring_to_Lead.cfm

2. American Association of Physics Teachers. (2017, May). K12 Programs-Aspiring to Lead. Retrieved June 1, 2018, from https://www.aapt.org/k12/Aspiring_to_Lead.cfm

Disclaimer – The articles and opinion pieces found in this issue of the APS Forum on Education Newsletter are not peer refereed and represent solely the views of the authors and not necessarily the views of the APS.