History of MURA, Fermilab, and the SSC

By Michael Riordan

On Sunday afternoon, May 4, the Forum co-sponsored with the Division of Physics of Beams a session on the "History of MURA, Fermilab and the SSC." Ably chaired by Gloria Lubkin, it emphasized proton accelerators and colliders in the central portions of the United States. Over 100 people attended, participating in the question-and-answer sessions after each talk.

Larry Jones of the University of Michigan led off with "Innovation Was Not Enough," a history of the fixed-field alternating-gradient (FFAG) proton accelerator proposed by the Midwestern Universities Research Association (MURA) in the mid-1950s. This project originated in reaction to the AEC's lavish funding of particle accelerators on both US coasts, which overlooked the Midwest. MURA even began to consider proton-proton colliding beams in 1956. But the project never got beyond the planning and prototyping stages, largely because of political pressures. The decision to build the Zero-Gradient Synchrotron at Argonne "really took the wind out of MURA's sails," recalled Jones. Nevertheless, MURA physicists made significant contributions to the understanding of particle dynamics in high-intensity proton beams, which have influenced accelerator physics ever since.

Credit: Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory, courtesy AIP Emilio Segré Visual Archives, Physics Today Collection

Robert Wilson and Glenn Seaborg breaking ground at Fermilab, 1969.

Fermilab Archivist Adrienne Kolb spoke next on "Fermilab: The Ring of the Frontier, 1965-1978." A co-author of the recent book Fermilab (see review in the Spring 2009 issue of the Newsletter, p. 10), she confined her remarks to the laboratory's first decade—including its construction—under Robert R. Wilson. A visionary physicist from Frontier, WY, by way of Berkeley and Cornell, he viewed accelerators as the "cathedrals of the modern age," Kolb said, "bringing people together to worship at the altar of Nature." She laced her lecture with a discussion of how "the frontier" became part of the rhetoric of high-energy physics during the 1960s and 1970s. In response to a question before the Joint Committee on Atomic Energy, about what the proposed National Accelerator Laboratory had to do with national defense, Wilson made his famous remark that it had "only to do with the respect with which we regard one another, the dignity of men, our love of culture . . . . It has nothing to do directly with defending our country, except to make it worth defending." Wilson succeeded in building NAL's Main Ring in 1972, under budget and ahead of schedule, but serious problems with its dipole magnets, many of which shorted out and had to be replaced, delayed the startup of its physics program for over a year. Kolb described those trying times in graphic detail, as "bundled-up teams worked in the cold and rain, sharing space with raccoons, spiders and snakes." Fermilab began to hit stride in the mid-1970s after the proton energy reached 400 GeV and an experimental team led by Leon Lederman of Columbia University discovered the upsilon particles in 1977—the earliest evidence for a predicted fifth quark known as the bottom quark. Wilson resigned as Director in 1978, in part to protest the restrictive Department of Energy funding of Fermilab. Lederman replaced him, ushering the laboratory into its second era, when the Main Ring was upgraded with superconducting magnets and converted into the highly productive Tevatron proton collider.

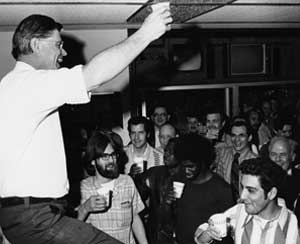

Credit: AIP Emilio Segré Visual Archives, Physics Today Collection

Robert R. Wilson (left), director of the National Accelerator Laboratory, Batavia, Ill., offers a toast to fellow employees when the accelerator reached its design energy of 200 GeV, 1 March 1972.

Stan Wojcicki of Stanford University wrapped up the session with a riveting account on the "History of the Supercollider: A Personal Recollection." He had played central roles in this abortive project, serving as Chair of a 1983 subpanel of the High-Energy Physics Advisory Panel (HEPAP) that recommended pursuing it, next as Associate Director of the SSC Central Design Group (CDG) at Lawrence Berkeley Lab, and finally as the Chair of HEPAP during the SSC construction phase. Few, if any, can speak with such authority on the subject (see his article "The Supercollider: The Pre-Texas Days—A Personal Recolletion of Its Birth and Berkeley Years, " Reviews of Accelerator Science and Technology 1, 259 (2008)). Wojcicki emphasized the "remarkable speed of the conceptual design process" at CDG, which took less than three years, and the highly effective management of that effort by Maury Tigner. But the selection of the SSC Director was rushed and poorly executed. As Wojcicki noted, "It is curious that no member of CDG was ever consulted during the Director choice process." The new SSC management under SSCL Director Roy Schwitters had a more conservative design philosophy that led to major cost increases when the site-specific design for Texas was developed. At that juncture, a key question arose about whether to descope the project to hold costs down; but the decision was made not to do so, and the total project cost ballooned nearly 40 percent to $8.25 billion. As the session ended, the audience joined a spirited discussion of reasons for the SSC's 1993 termination—among them the continuing cost increases and lack of any major foreign participation. This debate will doubtless continue for years to come.

Note Added: This article represents the views of the author, which are not necessarily those of the FHP or APS.