Spotlights on Outreach and Engaging the Public

ARTIFICE at the University of Chicago

Graduate students, technology, and the neighborhood

Reprinted with permission from the University of Chicago

Originally published on 18 Aug 2015

By Mary Abowd

Photo: Andrew Nelles

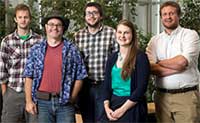

Artifice founders Adam Hammond, James Crooks and Ashley Lane (center) stand with graduate students Will McFadden (far left) and Pete Dahlberg (far right). The group is the driving force behind the nonprofit’s STEM education efforts in the Woodlawn neighborhood [of Chicago].

Photo: Robert Kozloff

LaShon Patterson, 19, a sophomore at Kennedy-King College, works with Ray Elementary School students, 11-year-olds Jeice Harris, center, and Henry Samra.

Photo: Jean Lachat

James Crooks, a PhD student in Biophysical Sciences, works with 12-year-old Darnell Smith at Artifice.

Photo: Robert Kozloff

Nine-year-old Shipharh Carney is absorbed in her task at the Artifice technology center in Woodlawn. The center provides youth with technical instruction so they can learn a variety of skills such as building websites and learning programming code.

Photo: Robert Kozloff

These donated electronics are tools instructors use to teach neighborhood students. Adam Hammond, PhD’01, director of curriculum in the Graduate Program in Biophysical Sciences, says kids can learn by taking them apart to understand how they're built.

Pete Dahlberg stands before a classroom of eager elementary school students. He’s poured liquid nitrogen into a deep steel pot, and the resulting steamy vapor makes this PhD student in Biophysical Sciences appear a wizard wielding a magic brew.

Dahlberg’s magician status derives from his participation in Artifice, a nonprofit organization dedicated to STEM education and staffed largely by University of Chicago doctoral students in the Graduate Program in Biophysical Sciences.

They teach at the organization’s headquarters, a community tech center in the Woodlawn neighborhood [of Chicago] where local youth learn to create websites, make video games, build robots, and repair computers.

But they also take their mission into local schools. On this day, students at William H. Ray Elementary School in Hyde Park surround Dahlberg. He invites them to add cream and sugar; then he stirs, sprinkling in science questions while the concoction thickens.

“Who knows the freezing point of water?” Dahlberg asks. The students peer into the pot; they can see that liquid nitrogen, at minus 321 degrees Fahrenheit, is much, much colder—cold enough to freeze cream and sugar practically on the spot. A few more seconds of stirring and poof! Dahlberg is serving up ice cream.

“We try to make the learning tactile and the technology fun and accessible,” says Dahlberg, who co-taught the 20-week, after-school course with fellow doctoral student Will McFadden. (The two also taught a course at the University of Chicago Charter School Woodlawn campus.)

Additionally, students in the course learned how to build home security systems and constructed and programmed “battle bots” (small robots equipped with razors and a balloon that turn, spin, and skirmish to see which bot’s balloon pops first). “The focus is not so much on how electrons are moving through the wires,” Dahlberg adds, “but more on, ‘wow, I can make an alarm go off or make something move.’”

From a pilot to a nonprofit

Artifice began two years ago as the vision of doctoral student James Crooks, a computer programmer and physicist, and Ashley Lane, AB’11, who was familiar with STEM initiatives through her work with nonprofits serving at-risk youth. “I saw projects that weren’t going to change anyone’s trajectory,” Lane says, “projects where the outcome was making a T-shirt.”

She and Crooks approached Adam Hammond, PhD’01, director of curriculum in the Graduate Program in Biophysical Sciences. The three imagined a neighborhood center for youth that could empower them to find jobs in an expanding technology sector or simply to use technology to help attain other goals. “Back then this was all just speculation, a what-if,” Crooks says. “We never intended to start a nonprofit.”

But once they put the word out, the community responded quickly. The UChicago Office of Civic Engagement, through its Community Programs Accelerator, helped Artifice find space and eventually helped them forge a partnership with Woodlawn East Community and Neighbors, which provides a storefront at 6460 S. Stony Island Ave. Other UChicago departments donated used computers, and a TV segment that aired on [the local public television station] WTTW-Channel 11 helped secure office furniture and other resources. By December 2013, a two-week pilot program was launched with students from Hyde Park Career Academy, yielding the center’s first wave of young techies.

Crooks says he and his co-founders knew two years ago they were onto something good when the pilot ended and the students were hungry for more. “The overwhelming feedback we got from the teens was that they didn’t want it to end; they wanted more instruction,” he says.

Constructing and deconstructing

Now on weeknights between 3:30 and 6 p.m. and Saturdays from 11 a.m. to 3 p.m., the center’s side door is propped open, and neighborhood kids ages 10 and up drop in for classes or free exploration at any of the center’s 12 computers.

Hammond, Dahlberg, Crooks, and a host of other graduate students, and some undergraduates, rotate teaching classes, tutoring, and simply being present to help kids, and even some adults, with whatever interests they bring in the door.

On any given day, Artifice has a makerspace vibe. “You might see kids making their own electromagnets, taking apart a 1990s Mac, or playing Minecraft,” says Hammond. “I might say to the kids, ‘I want all of the resistors out of this motherboard,” he adds. “The ‘take-this-apart’ approach is a great way to learn.”

DaQuohn Owney, who dropped into Artifice on the first day it opened, didn’t expect to like it. “I’m a writer,” he explains, “and I want to be an actor.” But technology caught fire with Owney, a senior at Hyde Park Career Academy, who now is able to maneuver among three different coding systems—HTML, CSS, and JavaScript—and has become skilled enough to work as an assistant teacher, mentoring younger participants.

Reciprocal benefits

In a sense, Artifice owes its ongoing work to the National Science Foundation’s highly competitive Research Traineeship Program. The program funds top doctoral students in the sciences who demonstrate not only intellectual merit but also a strong commitment to community engagement—what the foundation calls “broader impact.”

As NSF research fellows, Crooks, Dahlberg, and Ryan Mork devote several hours a week to Artifice, in addition to the rigorous research agendas they pursue in their respective labs.

“The National Science Foundation wants to give money to people who aren’t just going to be successful scientists but scientists with a capital ‘S’ and an exclamation point—the public figures, those who are going to really make a difference and have a broader impact in society,” says Hammond, who devotes several hours to Artifice each week.

As a successful nonprofit, Artifice also provides an edge in the increasingly competitive landscape of federal grants. “This project is valuable, and it’s a good thing to be doing,” says Tobin Sosnick, director of the Graduate Program and chair of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. “We also reap a huge reward in that it helps distinguish our students and tips [grant awards] in their favor.”

Owney has discovered the advantages of his newfound skills by transferring his coding knowledge to his own interests. “I like to try new things, and if I like something, I want to know all about it,” he says. His ambition to learn provided him with the tools to create a website, a resource for actors containing style tips, a blog, and celebrity news.

It’s precisely the kind of outcome Artifice’s co-founders had hoped to inspire. “One of our goals is to help kids figure out how to use technology to do what they want to do,” Crooks says, “to use it as a tool in whatever path they choose.”