Preserving the Manhattan Project

Articles

Cynthia C. Kelly

This year is the 65th anniversary of the dropping of atomic bombs on Japan and the end of World War II. While most people know about the atomic bombs, few people know what the Manhattan Project was or where it took place. The majority of the 125,000 Manhattan Project workers did not know about the bomb until the day the first one was dropped on August 6, 1945, and for decades thereafter much of the work of the Project remained shrouded in secrecy. Production facilities and laboratories were located "behind the fence," where only those with the proper security clearances were allowed. By the early 1990s, hundreds of Manhattan Project properties were slated to be destroyed as part of a nationwide cleanup of former nuclear weapons facilities. Few members of the public were aware that almost all that remained of this important chapter of history would soon be lost.

This article tells the story of efforts to preserve a few of the most important Manhattan Project properties. These efforts represent collaborative work between federal agencies including the Department of Energy and the National Park Service, State and local governments and historical societies, and other organizations. My six years with the Department of Energy alerted me to the dangers posed to the Manhattan Project properties and prompted me to found the Atomic Heritage Foundation (AHF) in 2002 to help preserve them.

The story begins in 1997, when the last remaining buildings at Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL) where the work of the Manhattan Project had taken place were slated for demolition. The original technical buildings around Ashley Pond had been torn down more than thirty years earlier. Now the rest were on the "D&D" or "demolition and destruction" list. About fifty original Manhattan Project properties were scattered behind the security fence in remote parts of the Laboratory. Isolated in space and time, few people even knew these buildings existed. While the Laboratory was required to keep the memory of historic properties by prescribed documents and photographs, preservation was not considered an option.

Most of the Manhattan Project properties were built to last only for the duration of the war and had been abandoned in mid-1950s. Among them was a cluster of humble wooden buildings called the V Site on a mesa that is surprisingly bucolic. Ponderosa pines tower above the structures and occasional herds of mule deer trot across the surrounding meadows. By the mid-1990s, nature had begun its own process of demolition. The roofs leaked and earthen mounds built as protection from possible explosions had broken through portions of the interior wall and dirt covered the floor. The high-bay doors that once swung open for the "Gadget," the world's first atomic device tested on July 16, 1945, were badly weathered.

In its report to New Mexico's environmental authorities on the V Site buildings, the Laboratory cited contamination with asbestos shingles and possible residues of high explosive materials. Apparently, the fact that the Laboratory determined that the buildings were contaminated was reason enough for State authorities to allow their demolition as part of the cleanup program. Working for the Department of Energy's environmental management program in Washington, DC at the time, I learned about their impending demolition. Alarmed that these properties might be lost, I called the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation (ACHP), a small Federal agency that advises the President and Congress and is the arbitrator of important preservation issues. John Fowler, the Council's long-standing executive director, was immediately interested in the plight of the Manhattan Project properties. Since the Council was planning to meet in Santa Fe in early November 1998, Fowler proposed that the Council members spend a day at Los Alamos.

When the Council members toured the V Site properties on November 5, they were struck by the contrast between the simplicity of the structures and the complexity of what had taken place inside them. Designing the world's first atomic bomb was the most ambitious scientific and engineering undertaking in the twentieth century, yet the buildings put up hastily in the summer of 1944 more closely resembled a common garage or work shed. Bruce Judd, an architect whose parents had worked on the Manhattan Project at Los Alamos, commented that the V Site properties were "monumental in their lack of monumentality." Who could believe that the world's first atomic bomb was designed and assembled in such an unimpressive structure? The birthplace of the atomic bomb was humble, like the garage in Palo Alto, CA where Bill Hewlett and David Packard invented one of the world's first personal computers in 1938.

Another Council member present was Carol Shull, the Keeper of the National Register of Historic Places for the National Park Service. In her judgment, the V Site properties not only qualified as a National Historic Landmark, of which there are fewer than 2,500, but also as a World Heritage Site. Today the United Nations has designated 890 World Heritage Sites such as the Acropolis in Athens, Machu Pichu, the "Lost City of the Incas," in Peru, and the ancient city of Petra in Jordan. Somewhat chastened, LANL management agreed to remove all of the V Site buildings from the demolition list. However, funds for restoration would have to come from some other source.

Photos courtesy Cindy Kelly.

Los Alamos V-site before and after restoration.Caption.

Fortunately, Congress had set aside $30 million under the new Save America's Treasures program to commemorate the millennium by preserving significant Federal properties that were in danger of being lost. Under the guidance of Secretary Bill Richardson, the Department of Energy competed for the new Save America's Treasures grants. The Department submitted seven applications, of which two were funded: $700,000 for the Los Alamos Manhattan Project properties and $320,000 for the Experimental Breeder Reactor–I in Idaho, the first test reactor built by the Atomic Energy Commission in 1951.

At Christmas time in 1999, the Save America's Treasures winners were honored at the White House. A little wooden replica of the V Site carved by a laboratory employee decorated a mantle in the green room. To raise the required matching funds for the Save America's Treasures grants, I left the Federal government and soon founded the Atomic Heritage Foundation. I soon learned how hard it was to raise funds for properties that were owned by the federal government and not easily accessible to the public. Many prospective donors believed that the government should pay for the restoration of its own properties. Because National Park Service officials wanted this first Save America's Treasures program to succeed, they took a liberal approach in considering what qualified as an in-kind donation. Eventually we were able to get credit for over $450,000 in in-kind donations.

At the Laboratory, John Isaacson and Ellen McGehee directed award-winning restoration work at the V Site. In 2006, the Atomic Heritage Foundation joined LANL and many other partners to celebrate the Site's restoration. On May 1, 2007, the State of New Mexico provided a Heritage Preservation Award "for the exemplary restoration of the V Site of the Manhattan Project, which successfully challenged the boundaries of preservation." On October 23, 2008, the National Trust for Historic Preservation also recognized the project with an award. Today, V Site is a touchstone for the Laboratory, a place where new employees and important visiting dignitaries are brought to learn about the Laboratory's history. While three of the buildings were destroyed by the Cerro Grande fire in 2000, the remaining two give the Manhattan Project a tangible reality. Through them, we are connected to the "galaxy of luminaries" recruited by J. Robert Oppenheimer to build the world's first atomic bombs. When we stand within its walls, we can imagine Oppenheimer and his colleagues inspecting the "Gadget" as it hung from the metal hook above our heads.

Inspired by the restoration of the V Site, in 2000 the Department of Energy listed eight properties as Signature Facilities of the Manhattan Project. The list included the V Site and Gun Site at Los Alamos, the X-10 Graphite Reactor, Beta-3 Calutrons and K-25 Gaseous Diffusion Plant at Oak Ridge, and the B Reactor and T Plant at Hanford. This was a major step forward but did not guarantee the preservation of these facilities. Thanks to the work of the B-Reactor Museum Association, however, that facility was subsequently declared a National Historic Landmark in 2008 (P&S, January 2010).

Photos courtesy Cindy Kelly.

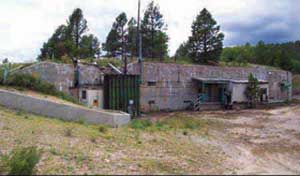

Los Alamos “Gun site,” currently under restoration. It is expected to be ready for visitors in about two years

The Foundation submitted its report to the Department of Energy on August 3, 2004. The report was also published as part of the Atomic Heritage Foundation's volume Remembering the Manhattan Project (World Scientific, 2004). The report's most important recommendation was to create a Manhattan Project National Historic Park at the three major Manhattan Project sites. Other recommendations urged that oral histories be taken of the surviving Manhattan Project veterans and that first-of-a-kind equipment and artifacts be preserved. The plan also listed properties that were essential to tell the story of the Manhattan Project at each of the major sites.

In September 2004, Congress passed the Manhattan Project National Historical Park Study Act [PL 108-340] that authorized the National Park Service to study whether to create a Manhattan Project National Historical Park. In December 2009, the National Park Service recommended a Manhattan Project National Historic Park at Los Alamos, NM but not at Oak Ridge, Hanford or Dayton, Ohio, which were all part of the study. (Dayton was included because that is where the polonium-beryllium "initiators" for the bombs were made.) The draft report argued that it was not feasible for the National Park Service to maintain or ensure the safety of the public or employees in radioactively contaminated facilities such as B Reactor or the uranium enrichment plants at Oak Ridge. Even the V Site along with other Manhattan Project properties owned by the Los Alamos laboratory was excluded.

In response, Congressmen, State and local government officials and the public deluged the National Park Service with letters in favor of including Oak Ridge and Hanford as units of the National Historical Park. Tennessee Senators Alexander and Corker wrote that "It would be impossible to tell the full story of the Manhattan Project without including all of the sites which made the project a success." At the same time, the Department of Energy clarified its commitment to maintain its Manhattan Project properties in perpetuity. In a letter dated May 13, 2010, Assistant Secretary for Environmental Management Ines Triay proposed a "strong and permanent partnership" with the National Park Service. As the nation's storyteller, the National Park Service could interpret the history and educate the public, while the Department of Energy would ensure visitor and employee safety.

This fall, the National Park Service is expected to submit its recommendations to Congress for a park with units at Los Alamos, Oak Ridge and Hanford. Over time, a number of affiliated areas could be created at the University of Chicago, University of California at Berkeley, Wendover Air Force Base in Utah, the Trinity Site at Alamogordo, NM, and sites in Dayton and on Tinian Island. With the likely designation of a Manhattan Project National Historical Park, the Atomic Heritage Foundation is planning to develop a national traveling exhibition on the Manhattan Project and its legacy. With oral histories, audiences will be able to hear first-hand accounts from Manhattan Project participants. The exhibition will address the Manhattan Project, Cold War and the continuing challenges of dealing with nuclear weapons today. In addition, a website will offer a "virtual tour" and a variety of programming and educational resources.

In the meantime, the AHF is continuing its work to preserve key Manhattan Project properties. A top priority is to ensure that at least a portion of the half-mile long K-25 plant in Oak Ridge is preserved. For the past few years, the Department of Energy has maintained that preserving a portion of the plant would be too dangerous and expensive. More than one-third of plant has already been razed. In May 2010, the Tennessee Trust for Historic Preservation named the K-25 plant as one of the state's ten most endangered historic sites. However, with increasing prospects for a Manhattan Project National Historic Park, the Department is taking a "second look" at the K-25 plant. An expert evaluation underway may prove that a piece can be cost-effectively and safely preserved for future generations. A second preservation priority is the Gun Site (TA-8-1) at Los Alamos, where Manhattan Project scientists and engineers developed and tested the uranium-based weapon design and assembled the Hiroshima Little Boy bomb. In FY 2010 Congress provided $500,000, and Clay and Dorothy Perkins of San Diego have pledged $250,000 for restoration of the bunker-like buildings, a 45-foot periscope tower, and a Naval cannon and their housings.

For more information about the history and preservation plans for Los Alamos, please see our recent Guide to the Manhattan Project Sites in New Mexico. Given the reception for this publication, we hope to publish similar guides to Project sites in Tennessee and Washington in the near future. In addition to the guidebooks, our anthology, The Manhattan Project: The Birth of the Atomic Bomb in the Words of Its Creators, Eyewitnesses, and Historians (Black Dog & Leventhal Press, 2007), traces the history with numerous historical documents and lively first-hand accounts of Manhattan Project history.

Over the past decade, the Foundation has been fortunate to work in partnership with Federal, State and local governments, historical societies, academia, and corporate and nonprofit organizations to preserve this remarkable past. With the prospective Manhattan Project National Historical Park, our vision of having some tangible remains from the Manhattan Project for future generations may become a reality. When future generations look back on the 20th century, few events will rival the harnessing of nuclear energy as a turning point in world history. Having some of the authentic properties where the Manhattan Project scientists and engineers achieved this is essential. As Richard Rhodes has said, "When we lose parts of our physical past, we lose parts of our common social past as well."

Cynthia Kelly is the President of the Atomic Heritage Foundation

These contributions have not been peer-refereed. They represent solely the view(s) of the author(s) and not necessarily the view of APS.