A Buddy-system of Physicists and Political Scientists

Thomas Colignatus

The USA is only proto-democratic. More than a third of US voters have taxation without representation. A buddy system of physicists and political scientists may clear up confusions and would likely have a positive impact on society.

Summary and introduction

World society has a worrying trend of threats to notions and systems of democracy, see Wiesner et al. (2018) in the European Journal of Physics. It might be a fair enquiry whether physicists might play a role in enhancing democracy, also in their off-physics-research moments. Physicists have scientific training with a focus on empirics and a command of mathematics and modeling, and they would be ideally placed in providing sound reasoning and debunking confusion, potentially also in off-physics discussions about democracy. However, whatever this ideal position, when physicists don’t study democracy then they are likely to be as uneducated as other people. One would expect that the true experts are political scientists, who might provide for such education also for physicists. This article will show however that political science still appears to be locked in the humanities on some crucial issues. Such political science rather creates confusion in the national educational system and the media, instead of providing the education that a physicist would need. The suggestion here is that the APS Forum on Physics and Society helps to set up a buddy system of physicists and political scientists so that the buddies – for all clarity consisting of a physicist and a political scientist per team – can educate and criticise each other in mutual respect, not only to each other’s enjoyment, but likely with positive impact on society.

Democracy is a large subject, and the present article focuses on electoral systems. I will present some findings that are new to political science on electoral systems, and these will be indicated by the label News. They provide good points of departure when a physicist would begin a discussion with his or her political science buddy.

Why would physicists be interested in electoral systems?

Physicists meet with elections once in a while. Within faculties and professional organisations sometimes formal voting procedures are used. In such cases, often the actual decision has already been made in (delegated) negotiations so that the formal voting procedure only serves for ratification and expression of consent by the plenum. Physicists may also vote in local, state or national elections, in which, one would hope, the outcome has not been predetermined. The often implicit suggestion is that such electoral systems have been well-designed so that they no longer need scrutiny. However, the highly worrying and disturbing diagnosis provided in this article is that countries like the USA, UK and France appear to be only proto-democratic. They are not the grand democracies as they are portrayed by political science in their books, the media and government classes in highschool. Physicists might be as gullible as anyone else who hasn’t properly studied the subject. Physicists might consider to rely upon mathematicians who write about electoral systems but mathematicians tend to lack the training on empirical research and create their own confusions, see Colignatus (2001, 2014). Physicists might however be amongst the first scientists who would be able to perceive that proper re-education would be required, and that the creation of said buddy system would be an effective approach, and perhaps even a necessary approach given the perplexities in the issue.

The US midterms of November 6 2018 allow for an illustration of a new finding from August 2017. This new insight is a game changer, compare the news that the Earth is not flat but a globe. Policy makers might need more time to adapt US electoral laws but the new information can be passed on quickly. It appears that more than a third of US voters have taxation without representation. It presents a problem that buddies of physicists and political scientists can delve into, to each other’s perplexion.

Discovery in August 2017

Some readers will be familiar with the distinction between “district representation” (DR) versus “equal proportional representation” (EPR). In DR the votes in a district determine its winner(s) regardless of national outcomes. In EPR parties are assigned seats in equal proportion to the vote share, with particular rules to handle integer numbers. Before August 2017 I thought that the properties of DR and EPR were well-known, and that the main reason why the USA, UK or France did not change from DR to EPR was that a party in power would not easily change the system that put it into power. Then however I discovered that the literature in the particular branch of “political science on electoral systems” (including referenda) did not discuss the properties with sufficient scientific clarity. Many statements by “political science on electoral systems” are still locked in the humanities and tradition, and they aren’t scientific when you look at them closely. For its relevance for empirical reality this branch of political science can only be compared to astrology, alchemy or homeopathy. The 2018 proof is in paper 84482 in the Munich archive MPRA, Colignatus (2018a). Thus the academia have been disinforming the world for the greater part of the last century . Americans express a preference for their own political system – an excellent book in this respect is Taylor et al. (2014) – but they are also indoctrinated in their obligatory highschool Government classes, which in their turn again are disinformed by the academia, like indeed Taylor et al. too . Rein Taagepera (born 1933) started as a physicist and continued in political science with the objective to apply methods of physics. Shugart & Taagepera (2017) present marvels of results, yet run aground by overlooking the key distinction between DR and EPR, as discussed here. Let us now look at the US midterm of 2018, and apply clarity.

US House of Representatives 2018

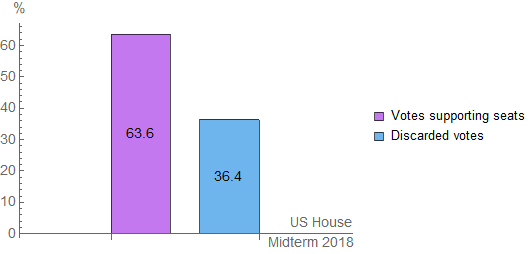

In the 2018 Midterms for the US House of Representatives, 63.6% of the votes were for winning candidates and 36.4% were for losing candidates, see the barchart. This chart is novel and is conventionally not shown even though it is crucial to understand what is happening. The US system of district representation (DR) has “winner take all”. The traditional view is that the losing votes are “wasted”. Part of the new insight is that the latter terminology is distractive, too soft, and falsely puts the blame on the voter (who should be wiser than to waste his or her vote). In truth we must look at the system that actually discards these votes. These votes no longer count. These voters essentially have taxation without representation.

Legal tradition in the humanities versus empirical science

Economic theory has the Principal – Agent Theory (PAT). Supposedly the voter is the principal and the district representative would be the agent. However, a losing voter as principal will hardly regard a winning candidate as his or her agent. The legal storyline is that winning candidates are supposed to represent their district and thus also those who did not vote for them. Empirical science and hardnosed political analysts know that this is make-believe with fairy tales in cloud cuckoo land. In practice, losing voters in a district deliberately did not vote for the winning candidate and most losing voters commonly will not regard this winner as their proper representative but perhaps even as an adversary (surely this cannot be News? But textbooks in political science do work the point). The textbook by Taylor et al. (2014) refers to PAT but applies it wrongly as if legal formality suffices. Under the legal framing of “representation” these House winners actually appropriate the votes of those who did not vote for them. Rather than a US House of Representatives we have a US House of District Winners, but we might also call it the US House of Vote Thieves.

These voting outcomes are also highly contaminated by the political dynamics of district representation (DR). The USA concentrates on bickering between two parties, with internal strife and hostile takeovers in the primaries (Maskin & Sen (2016)). Many voters only voted strategically in an effort to block what they considered a worse alternative, and originally had another first preference. In a system of equal proportional representation (EPR) like in Holland, there is “electoral justice”. Holland has 13 parties in the House and allows for the dynamic competition by new parties. Voters are at ease in choosing their first preference and thus proper representatives. They might also employ some strategy but this would be in luxury by free will. In the USA voters often fear that their vote is lost, and the outcome is also distorted by their gambling about the odds. Thus we can safely conclude that even more than a third of US voters in 2018 are robbed from their democratic right of electing their representative.

Legal tradition versus the Universal Declaration of Human Rights

Article 21 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) of 1948 states: “Everyone has the right to take part in the government of his country, directly or through freely chosen representatives.” When votes are not translated into representation of choice, then they are essentially discarded, in violation of this human right. The USA helped drafting and then ratified the UDHR but apparently did not realise that its own electoral system violates it . The USA has been saved somewhat by the workings of the Median Voter Theorem and by parties defending their voters in losing districts (which runs against the principle of representing your own district. The loss of economic well-being must be great , e.g. compare Sweden and Holland, that switched from DR to EPR in 1907 resp. 1917, that are among the happiest countries. [1]

Confirmation by a scatter plot

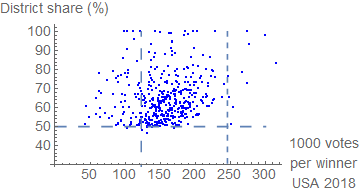

We see this diagnosis confirmed by the district results of the US Midterms, see the scatter chart with horizontally the number of votes per winner and vertically the share of that winning vote in the district. Some districts are uncontested with 100% of the share. The key parameter is the electoral quota, defined as the total number of votes divided by the 435 seats in the US House. This is about 246 thousand votes, given by a vertical dashed line.

In EPR a seat in the House would be fully covered by this electoral quota, and practically all dots would lie on this line except for some remainder seats. In DR in the USA in 2018 only some 11 dots manage to reach this quota, helped by having large districts. Gerrymandering can help to create such districts. There can be more districts with fewer voters in which the gerrymandering party hopes to have an easier win, remarkably often with even less than half the electoral quota at 123 thousand. While some people speak out against gerrymandering, it is the very point of having districts itself that disenfranchises voters.

In the USA the winners tend to gain more than 50% of the votes in their districts, which plays into the storyline that they gain a majority in their district, but this still is a make-believe fairy tale because they fall brutally short of the electoral quota for proper representation. That winners tend to get more than 50% merely reflects the competition between only two parties, at the detriment of other views.

Ordinary language instead of scientific precision

Above observation on taxation without representation could be an eye-opener for many . Perhaps two eyes may be opened. This unscientific branch of political science relies upon ordinary language instead of definitions with scientific precision . Physics also borrowed common words like “force” and “mass”, yet it provided precise definitions, and gravity in Holland has the same meaning as gravity in the USA. The “political science on electoral systems” uses the same words “election” and “representative” but their meaning in Holland with EPR is entirely different from the USA with DR. We find that the USA, UK and France are locked into confusion by their vocabulary. The discussion above translates into the following deconstruction of terminology .

- In EPR, we have proper elections and proper representatives. Votes are bundled to go to their representative of choice (commonly of first preference), except for a small fraction (in Holland 2%) for tiny parties that fail to get the electoral quota. Those votes are wasted in the proper sense that the technique of equal proportionality on integer seats cannot handle such tiny fractions. A solution approach to such waste is to allow alliances (“apparentement”) or empty seats or at least to require qualified majority voting in the House.

- In DR, what is called an “election” is actually a contest . A compromise term is “election contest”. What is called a “representative” is rather a local winner, often not the first preference. (This is often recognised in the PS literature and thus no News, but remarkably political scientists then switch to the legality of representation and continue as if a winner is a representative indeed.) The legal terminology doesn’t fit political reality and Principal – Agent Theory .

An analogy is the following . Consider the medieval “trial by combat” or the “judgement of God”, that persisted into the phenomenon of dueling to settle conflicts. A duel was once seriously seen as befitting of the words “trial” and “judgement”. Eventually civilisation gave the application of law with procedures in court. Using the same words “judgement” and “trial” for both a duel and a court decision confuses what is really involved, though the outward appearance may look the same, i.e. that only one party passes the gate. It is better to use words that enhance clarity. The system of DR is proto-democratic while proper democracy uses EPR.

Shaun Lawson (2015) in the UK laments how elementary democratic rights are taken away but still doesn’t understand how. Now we know. The problem lies first of all with the academia .

Blame also the unscientific cowardice of R.A. Dahl and C.E. Lindblom

Both eyes might be opened even further by a glance at the US presidency, that currently occupies the USA so much, and that creates such needless national division. Arthur Schlesinger, “The Imperial Presidency”, 1973, was concerned that the US presidency exceeded its constitutional boundaries and was getting uncontrollable. Robert Dahl & Charles Lindblom, “Politics, Economics, and Welfare”, 1976, page 349, take this into account and provide their answer:

"Given the consequences of bargaining just described, what are the prerequisites of increasing the capacity of Americans for rational social action through their national government? (...) Certainly the adoption of a parliamentary system along British lines, or some version of it, may be ruled out, not only because no one knows enough to predict how it would work in the United States, but also because support for the idea is nonexistent. Although incremental change provides better opportunity for rational calculation than comprehensive alternations like substitution of the British system, there is little evidence even of a desire for incremental change, at least in a direction that would increase opportunities for rational calculation and yet maintain or strengthen polyarchal controls.”

This is a statement of unscientific cowardice. A scientist who observes climate change provides model, data and conclusion, and responds to criticism. Dahl & Lindblom show themselves as being afraid of stepping out of the line of tradition in the humanities. They fear the reactions by their colleagues. They want to keep saying that the US is a democracy rather than conclude that it is only proto-democratic. They resort to word-magic and present a new label “polyarchy” as a great insight while it is a cover-up for the failure on democracy (p276). The phrase about predicting how a parliamentarian system would perform in the USA is silly when the empirical experience elsewhere is that it would be an improvement (this cannot be News since the evidence exists but it might be News to political scientists that D&L close their eyes for the evidence). Nowadays, the US House of Vote Thieves can still appoint a prime minister. For this goverance structure, it is only required that the US president decides to adopt a ceremonial role, which is quite possible within the US constitution, and quite logical from a democratic point of view. For the checks and balances it would also be better that the (ceremonial) president doesn’t interfere with the election of the legislature, but we saw such meddling in 2018. See also Juan Linz, “The perils of presidentialism”, 1990. The reference by Dahl & Lindblom to Britain partly fails because it also has DR, while the step towards proper democracy includes the switch to EPR, also for Britain. See Colignatus (2018e) for an explaination how Brexit can be explained by the pernicious logic of DR and referenda, and for a solution approach for Britain to first study electoral systems, switch to EPR, have new elections, and then let the UK parliament reconsider the issue.

In his obituary of Dahl, Ian Shapiro stated in 2014: “He might well have been the most important political scientist of the last century, and he was certainly one of its preeminent social scientists”. Also the informative and critical Blokland (2011) does not deconstruct this image. The truth rather is, obviously with all respect, that Dahl was still locked in the humanities and tradition. He lacked the mathematical competence to debunk Kenneth Arrow’s interpretation of his “Impossibility Theorem”, see Colignatus (2001, 2014). Dahl’s unscientific cowardice has led “political science on electoral systems” astray , though political scientists remain responsible themselves even today. Scandinavia has EPR but its political scientists can still revere Dahl. Teorell et al. (2016) follow Dahl’s misguided analysis, and their “polyarchy index” puts the USA, UK and France above Holland, even while at least a third of US voters are being robbed from representation because of the US House of Vote Thieves. Hopefully also the Scandinavians set up a buddy system for their political scientists.

Incompetence may become a crime

If the world of political science would not answer to this criticism and burke it, then this would constitute a white collar crime. The US has a high degree of litigation that might turn this into a paradise for lawyers (not really news). Yet in science as in econometrics we follow Leibniz and Jan Tinbergen (trained by Ehrenfest), and we sit down and look at the formulas and data. Empirical scientists tend to be interested in other things than democracy, and when they haven’t studied the topic then they may have been indoctrinated in highschool like any other voter (not really News). Scholars who are interested in democracy apparently have inadequate training in empirics (this is News). Those scholars have started since 1903 (foundation of APSA) with studying statistics and the distinction between causation and correlation, but a key feature of empirics is also observation. When it still is tradition that determines your frame of mind and dictates what you see and understand, then you are still locked in the humanities, without the ability to actually observe what you intend to study. It is crucial to observe in DR that votes are discarded and are not used for representation of first preferences, unhinging the principal-agent relationship that you claim would exist. Also FairVote USA is part of the problem, who do not clearly present the analysis given here and who misrepresent equal proportionality by trying to make it fit with DR, while the true problem is DR itself. The USA is locked in stagnation.

A buddy-system of scientists and scholars from the humanities

The obvious first step is that real scientists check the evidence (at MPRA 84482), which would require that scientists in their spare time develop an interest in democracy, and that scholars in “political science on electoral systems” overcome their potential incomprehension about this criticism on their performance. The suggested solution approach is to set up a buddy-system, so that pairs of (non-political) scientists (physicists) and (political science) scholars can assist each other in clearing up confusions.

Some may fear what they might discover, and fear what they might have to explain to (fellow) US voters, but like FDR stated in 1933: There is nothing to fear but fear itself.

PM 1. The evidence for this article is provided in Colignatus (2018a) at MPRA 84482. Appendix A summarizes supplementary evidence by Colignatus (2018b). Appendix B discusses seeming inconsistencies in this article. For consequences for UK and Brexit, see Colignatus (2018d) in the October 2018 Newsletter of the Royal Economic Society. See Colignatus (2018e) for a suggestion of a moratorium.

PM 2. The data in the charts are from the Cook Political Report of November 12 2018, with still 7 seats too close to call but presumed called here.

PM 3. I thank Stephen Wolfram for the programme Mathematica used here. For the creation of Mathematica, Wolfram was partly inspired by the program Schoonschip by Martinus Veltman.

Appendix A. Supplementary evidence on inequality / disproportionality of votes and seats

The following is from Colignatus (2018b). Political science on electoral systems uses measures of inequality or disproportionality (ID) of votes and seats, to provide a summary overview of the situation. Relevant measures are (i) the sum of the absolute differences, corrected for double counting, as proposed by Loosemore & Hanby (ALHID), (ii) the Euclidean distance proposed by Gallagher (EGID), and (iii) the sine as the opposite of R-squared in regresssion through the origin, as proposed by me (SDID). For two parties, or when only one party gets a seat so that the others can be collected under the zero seat, then Euclid reduces to the absolute difference.

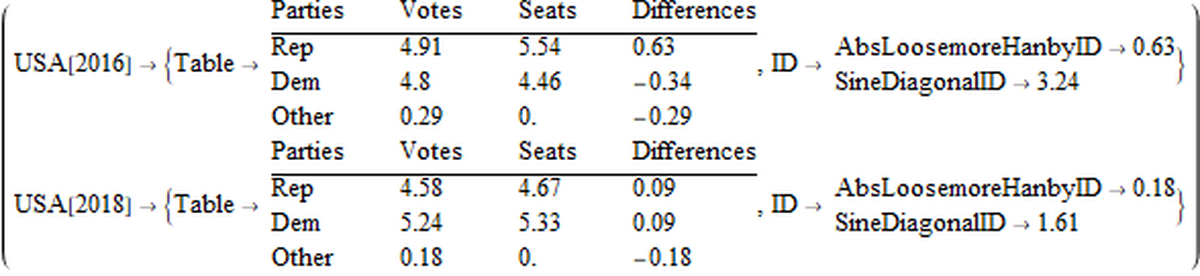

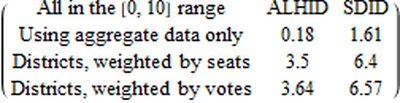

The following table gives the US data for 2016 and preliminary 2018. Conveniently we use data and indices in the [0, 10] range, like an inverted report card (Bart Simpson: the lower the better). The ALHID of 2016 gives a low value of 0.63 in a range of 10, but SDID provides a magnifying glass and finds 3.24 on a scale of 10. In 2018 the inequality / disproportionality seems much reduced. Observe that the votes are not for first preferences due to strategic voting, and outcomes thus cannot be compared to those of countries with EPR.

Taylor et al. (2014:145) table 5.6 give electoral disproportionalities in houses of representatives in 31 democracies over 1990-2010, using EGID. Proportional Holland has 0.1 on a scale of 10 (there is little need to measure something that has been defined as equal proportional), and disproportional France has 1.95 on a scale of 10. The USA has 0.39 on a scale of 10. Taylor et al. p147 explain the much better performance of the USA compared to France by referring to the US two-party-system, including the impact of the US primaries. This statement is curious because it doesn’t mention strategic voting and thus the basic invalidity of the measure. In 2018 more than a third of the votes in the USA are discarded, so their table 5.6 does some number crunching as if it were science but misses the key distinction between EPR and DR.

Taylor et al. may be thanked for their mentioning of the primaries, because this highlights that the USA labels of “Republican” and “Democrat” are only loosely defined. District candidates have different origins and flavours. A Southern Republican in 2018 may rather derive from the Southern parties who supported slavery and thus be less rooted in the original Republicans of Lincoln who abolished slavery in 1863. Condoleezza Rice may wonder which Republican Party she joined. Thus, above aggregate measures are dubious on the use of these labels too. In the aggregate we see that district winners are supposed to defend losers of the same party in other districts, but this runs against the notion that a representative ought to represent the own district. This objection is stronger when the party labels over districts are only defined loosely.

Thus, as an innovation for the literature, it is better to use the ALHID = EGID and SDID measures per district, and then use the (weighted) average for the aggregate. In each district there is only one winner, which means that the disproportionality is large, and we see more impact from the phenomenon that losing votes are not translated into seats. When we weigh by seats, or the value 1 per district, then we get the plain average. Alternatively we can weigh by the votes per district. We find that the 2018 aggregate ALHID of 0.18 rises to the average 3.50 (weighted by seats) or 3.64 (weighted by votes) on a scale of 10. SDID uses a magnifying glass. These outcomes are still distorted by strategic voting, of course, but the outcomes show the dismal situation for representation in the USA much better. In the best measure (SDID) on a scale of 0 (best) to 10 (worst), the USA is 6.57 off-target.

Thomas Colignatus is the scientific name of Thomas Cool, Econometrician (Groningen 1982) and teacher of mathematics (Leiden 2008), Scheveningen, Holland. http://thomascool.eu, ORCID 0000-0002-2724-6647. He is close to retirement without current professional affiliation, secretary of the Samuel van Houten Genootschap (the scientific bureau of an initiative for a new political party), and he publishes his books via Thomas Cool Consultancy & Econometrics.

Appendix B. Seeming inconsistencies

This article runs the risk of an inconsistency (A): (i) The information was known around 1900 so that Sweden and Holland could make the switch from DR to EPR, (ii) There is News for the political science community so that now the USA, UK and France can make the switch too. Formulated as such, this is a plain inconsistency. However, political scientists in the USA, UK and France invented apologies to neglect the information under (i). The News under (ii) debunks such apologies. Thus there is no inconsistency. There is a distinction between full information (with arguments pro and con) and an apology to neglect information. Sweden and Holland did not invent such apologies and thus were informed back then, and are not in need of debunking now. One might consider that Sweden and Holland were too rash in their switch from DR to EPR, since they overlooked such apologies to neglect information. This however would be like arguing that a proper decision also requires putting one’s head under the sand, at least for some 100 years, in order to see the full spectrum of possible choices.

This article runs the risk of inconsistency (B): (i) It is a strong claim that something is News, and this would require knowledge of all political science literature, (ii) The author is no political scientist. Formulated as such, this is a plain inconsistency. However, Colignatus (2018a) selects a political science paper that is “top of the line” and then debunks it. For all practical matters this is sufficient.

Colignatus (2001, 2014) discusses single seat elections. My intention was to write a sequel volume in 2019 on multiple seat elections, combining (2018a) and (2018b) and related papers. This present article is a meagre abstract of this intended sequel. I got sidetracked in 2018-2019 on the environment and climate change by assisting Hueting & De Boer (2019) and drafting Colignatus (2019).

The News in this article has not been submitted to political science journals, so that the underlying diagnosis maintains its validity for a longer while, i.e. that political science on electoral systems still is locked in the humanities. This News has been indicated to the board of the Political Science association in Holland, but they are likely unaware about the econometric approach to Hume’s divide between Is and Ought, see Colignatus (2018c), p6-7.

The News in this article has not been submitted to political science journals because the community of political science has had ample opportunity since 1900 to listen and we can observe as an empirical fact that they do not listen but invent apologies not to listen, and thus don’t do science properly. While Sweden and Holland switched from DR to EPR so early in the 1900s, the USA (“American exceptionalism”) and UK (“the world’s first democracy”) had the same discussion but kept DR, and the very manner of reasoning does not show rationality but traditionalism verging on mystic glorification of national history. France had a phase of EPR but then some political parties tried to stop the popular Charles de Gaulle by switching to DR, and they in fact created a stronger power base for the Gaullists. Instead of disseminating the News via a submission to a political science journal where it will be handled by methods of astrology, alchemy and homeopathy, it is better to call in the cavalry. Let the world observe the dismal situation of political science on electoral systems, and let the scientific community put a stop to it.

An example of a physicist looking at democracy is Karoline Wiesner. The paper Wiesner et al. (2018) is not presented as the final truth here. There is no guarantee that such study will be useful without the News provided here as points of departure. For example, their article uses the The Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) Index of Democracy, that does not catalog the proto-democratic electoral systems in the USA, UK and France as major threats to democracy.

References

Blokland, H.T. (2011), “Pluralism, democracy and political knowledge : Robert A. Dahl and his critics on modern politics”, Burlington, Ashgate

Boissoneault, L. (2017), “The True Story of the Reichstag Fire and the Nazi Rise to Power”, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/true-story-reichstag-fire-and-nazis-rise-power-180962240/

Colignatus (2001, 2014), “Voting Theory for Democracy”, http://thomascool.eu/Papers/VTFD/Index.html and https://zenodo.org/record/291985

Colignatus (2018a), “One woman, one vote. Though not in the USA, UK and France”, https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/84482/

Colignatus (2018b), “An overview of the elementary statistics of correlation, R-Squared, cosine, sine, Xur, Yur, and regression through the origin, with application to votes and seats for parliament ”, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1227328

Colignatus (2018c), “Letter to the board of NKWP, the Dutch Political Science Association”, http://thomascool.eu/Thomas/English/Science/Letters/2018-09-29-NKWP.pdf

Colignatus (2018d), “Brexit’s deep roots in confusion on democracy and statistics”, RES Newsletter 183, October, p18-19. http://www.res.org.uk/view/art1Oct18Comment.html

Colignatus (2018e), “A Brexit moratorium of two years for UK and EU to 2021”, https://boycottholland.wordpress.com/2018/12/07/a-brexit-moratorium-of-two-years-for-uk-and-eu-to-2021/

Colignatus (2019), “The Tinbergen & Hueting approach to the economics and national accounts of ecological survival”, draft indicated by the label News, meaning

Dahl, R.A. and C.E. Lindblom (1976), “Politics, Economics, and Welfare. Planning and politico-economic systems resolved into basic social processes”, Chicago

Hueting, R. and B. de Boer (2019), “National Accounts and environmentally Sustainable National Income”, Eburon Academic Publishers

Lawson, S. (2015), “When is a democracy not a democracy? When it’s in Britain”, https://www.opendemocracy.net/ourkingdom/shaun-lawson/when-is-democracy-not-democracy-when-it%E2%80%99s-in-britain

Linz, J.J. (1990), “The perils of presidentialism”, Journal of Democracy, Volume 1, Number 1, Winter 1990, pp. 51-69, http://muse.jhu.edu/journal/98

Maskin E, Sen A. (2016), “How Majority Rule Might Have Stopped Donald Trump” The New York Times, May 1

Schlesinger, A.M. (1973), “The imperial presidency”, Houghton Miffin

Shapiro, I. (2014), “Democracy Man. The life and work of Robert A. Dahl”, Foreign Affairs, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/2014-02-12/democracy-man

Shugart, M.S. and R. Taagepera (2017), “Votes from seats”, CUP

Taylor,S.L., M.S. Shugart, A. Lijphart, and B. Grofman (2014), "A Different Democracy. American Government in a 31-Country Perspective", Yale

Teorell, J., M. Coppedge, S.-E. Skaaning, and S.I. Lindberg (2016), “Measuring electoral democracy with V-Dem data: Introducing a new Polyarchy Index”, https://www.vdem.net/media/filer_public/f1/b7/f1b76fad-5d9b-41e3-b752-07baaba72a8c/vdem_working_paper_2016_25.pdf or https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2740935

Wiesner, K. et al. (2018), “Stability of democracies: a complex systems perspective”, European Journal of Physics, Vol 40, No 1

[1] Caveat: these countries must thank the USA and UK for saving them from the Nazis. A common line of argument is that DR protected the USA and UK from dictatorship, and that EPR allowed the Nazis to seize power. Instead, EPR made it more difficult for the Nazis, and they only got in control by the fire of the Reichstag and arresting communists in the Weimar parliament, see Boissoneault (2017). (This is not News since some specialists know this, but it still is not common knowledge amongst political scientists.)

These contributions have not been peer-refereed. They represent solely the view(s) of the author(s) and not necessarily the view of APS.